In March 1942, Charles W. Koerner replaced Joseph I. Breen as head of production at RKO. The previous July, George Schaefer had lured Breen away from the Hays Office to RKO, and ever since then Breen had served more or less as a rubber stamp for Schaefer's decisions.

Charles Koerner, however, was made of more contentious stuff. His background was in theater operation; before replacing Breen he had been head of RKO's exhibition arm in New York. In that position he had surely seen the theater owners' reports in Motion Picture Herald's "What This Picture Did for Me" column, and in the case of Citizen Kane the verdict had been "Nothing."

Koerner was the point man and chief organizer of those who were alarmed at RKO's march toward insolvency under Schaefer's stewardship; millions were gushing out of studio coffers, pittances trickling in. The studio had managed to climb out of receivership only in January 1940, and now it was in danger of falling back into it. Koerner was angling to get Schaefer out of the way, then to put RKO back on a sound financial footing, and he meant to curb what he and his allies saw as the studio throwing good money after bad.

Just to show how the wind was blowing, one of Koerner's first acts in his new Hollywood office was to send out a memo to the studio at large: The Magnificent Ambersons, Journey into Fear and It's All True would all proceed -- for now -- but everyone should check with him before entering into any new agreements with Orson Welles or Mercury Productions. Clearly, George Schaefer wasn't the only one whose days at RKO were numbered.

Koerner brought an exhibitor's perspective to his new job; it told him that the shorter the feature, the more showings per day and the more money a theater could make. Koerner also believed that the double feature was the wave of the future (giving credit where it's due, he was right; the double feature would outlast the studio system itself). He decreed that 90 minutes, give or take a few, was to be the target length for all RKO features, and this edict was conveyed to Robert Wise as he and Mark Robson toiled away on The Magnificent Ambersons.

Meanwhile, down in Rio, Orson Welles was devising his latest and last plan for recutting Ambersons. He transmitted his instructions to Jack Moss and Wise in a 30-page telegram on March 27. He probably didn't know about Koerner's 90-minute cap on feature length, but it may not have made any difference if he did.

Welles also called for cutting this shot, the iris-out on the horseless carriage as it trundles along in the snow with everyone singing "The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo". This would entail no substantial loss, but the iris-out is a truly lovely moment that evokes the period as vividly as any four seconds in the whole picture. Prof. Carringer calls cutting it "another great surprise", but I'd go further than that; I'd say it's a real head-scratcher, a cut that loses far more than the time it saves. I think, just maybe, if I'd been Robert Wise, I might have started to wonder if, in all the bustle and flurry of It's All True, Orson had perhaps begun to lose touch with the movie he was making before he flew off to Brazil. But never mind, that's just me thinking out loud; I don't want to put thoughts into Wise's 1942 head.

Charles Koerner, however, was made of more contentious stuff. His background was in theater operation; before replacing Breen he had been head of RKO's exhibition arm in New York. In that position he had surely seen the theater owners' reports in Motion Picture Herald's "What This Picture Did for Me" column, and in the case of Citizen Kane the verdict had been "Nothing."

Koerner was the point man and chief organizer of those who were alarmed at RKO's march toward insolvency under Schaefer's stewardship; millions were gushing out of studio coffers, pittances trickling in. The studio had managed to climb out of receivership only in January 1940, and now it was in danger of falling back into it. Koerner was angling to get Schaefer out of the way, then to put RKO back on a sound financial footing, and he meant to curb what he and his allies saw as the studio throwing good money after bad.

Just to show how the wind was blowing, one of Koerner's first acts in his new Hollywood office was to send out a memo to the studio at large: The Magnificent Ambersons, Journey into Fear and It's All True would all proceed -- for now -- but everyone should check with him before entering into any new agreements with Orson Welles or Mercury Productions. Clearly, George Schaefer wasn't the only one whose days at RKO were numbered.

Koerner brought an exhibitor's perspective to his new job; it told him that the shorter the feature, the more showings per day and the more money a theater could make. Koerner also believed that the double feature was the wave of the future (giving credit where it's due, he was right; the double feature would outlast the studio system itself). He decreed that 90 minutes, give or take a few, was to be the target length for all RKO features, and this edict was conveyed to Robert Wise as he and Mark Robson toiled away on The Magnificent Ambersons.

Meanwhile, down in Rio, Orson Welles was devising his latest and last plan for recutting Ambersons. He transmitted his instructions to Jack Moss and Wise in a 30-page telegram on March 27. He probably didn't know about Koerner's 90-minute cap on feature length, but it may not have made any difference if he did.

We can't know what the running time of Welles's March 27 cut would have been because it was never assembled, much less screened for an audience. Welles ordered some major changes from the last version he had called for, the one previewed in Pomona. In the Christmas ball scene, he wanted a dissolve from the moment when George and Lucy dance away from the camera (after she asks "What do you want to be?" and he replies "A yachtsman.") directly to the scene of Lucy and Eugene putting their horseless carriage away in the barn as they return home (a scene that is not in the release version). As Robert L. Carringer says, this would entail losing this shot of Eugene and Isabel dancing alone after all the other guests have gone, "what many regard as the single most beautiful shot in the film."

The shot is beautiful and evocative, but much more would have been lost if Welles had had his way. Also out would be the conversation between George and Lucy on the stairs (you can just glimpse them in the background coming down to take their seats on the steps) in which they banter about Eugene's automobile business ("Papa would be so grateful if he could have your advice." "I don't know that I've done anything to be insulted for!") and George presses Lucy for a sleighing date the next afternoon ("Tomorrow? I can't possibly go." "I'm going to sit in a cutter at your front gate and if you try to go out with anybody else he has to whip me before he gets to you."); the party breaking up as the Morgans prepare to leave; George quizzing Uncle Jack ("Who is this fellow Morgan?" "Why, he's a man with a pretty daughter, Georgie ... Do you take this same passionate interest in the parents of every girl you dance with?" "Oh, dry up!"); Lucy finally giving in on that date ("No, I won't." "Yes, you will. Ten minutes after two." "Yes, I will."); the goodbyes in the snow; and Lucy and Eugene talking about George and Isabel on the ride home ("You liked her pretty well once, I guess, Papa." "Do still.") Prof. Carringer marvels that Welles would contemplate cutting Eugene and Isabel dancing; personally, I'm amazed that he would cut everything else.

Welles also called for cutting this shot, the iris-out on the horseless carriage as it trundles along in the snow with everyone singing "The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo". This would entail no substantial loss, but the iris-out is a truly lovely moment that evokes the period as vividly as any four seconds in the whole picture. Prof. Carringer calls cutting it "another great surprise", but I'd go further than that; I'd say it's a real head-scratcher, a cut that loses far more than the time it saves. I think, just maybe, if I'd been Robert Wise, I might have started to wonder if, in all the bustle and flurry of It's All True, Orson had perhaps begun to lose touch with the movie he was making before he flew off to Brazil. But never mind, that's just me thinking out loud; I don't want to put thoughts into Wise's 1942 head.

I don't want to put thoughts into Welles's head either, but I have to speculate on why he was willing to trim so much meat (a little over four minutes) off the tail end of the ball scene after the "yachtsman" line. I suspect Welles was focused on preserving the sequence that made up the centerpiece of the Amberson ball -- the one that had consumed nine ten-hour days and occupied a crew of 100 to shift walls, doors and step units in and out of place as Tim Holt, Anne Baxter, Joseph Cotten, Ray Collins et al. strolled and chatted amid their splendid surroundings, alternately basking in them and taking them for granted.

The sequence is represented here by (top) a frame from the release version of Lucy and George strolling across the parquet floor, George wondering why so many "nobodies" at the ball seem already to know this young lady he's only just met; and (bottom) a production photo of a portion of the shot that didn't make the final cut, as George and Lucy climb to the third floor of Amberson Mansion, where the dancing and most of the celebrating are going on.

This series of long takes, so intricate and time-consuming to get on film, loomed large in Welles's heartsick memory of Ambersons. "It was the greatest tour de force of my career!" he told Barbara Leaming, and it may well have been. "The entire sequence was one reel without a single cut." Here, however, Welles's memory played him false. In fact, according to the 132-min. cutting continuity, the twelve-and-a-half minute sequence consisted of ten separate shots, the longest of which ran 376 feet, a little under four-and-a-quarter minutes. Even so, with all the choreographed movement of actors, sets and camera, it's no surprise that Welles remembered it as one long uninterrupted take. Nor is it surprising that he would want to preserve it. The scenes of the end of the ball that he wanted to cut run about a minute less than what was eventually cut out of that ten-shot sequence. The question is, did Welles want the earlier footage left in because it advanced the picture as a whole, or because he was proud of it as a technical and logistical achievement all by itself?

Welles was similarly protective of the boarding house scene that ended the picture ("much the best scene in the movie"). The loss of these two scenes -- the bookends, if you will, of The Magnificent Ambersons -- were what Welles most bitterly lamented for the rest of his life (along with that long tracking shot through the deserted Amberson Mansion that Stanley Cortez was so proud of -- Welles evidently having forgotten that he never included that shot in the first place). For what came between the bookends, Welles on March 27 had other, rather radical changes in mind.

Two scenes -- (1) the buggy ride scene, where George and Lucy quarrel over George's reluctance to "make something of himself", and (2) the following carriage scene between Uncle Jack and Major Amberson, talking about the changes in their town and the decline in the family fortune -- Welles wanted to move to much earlier, before Wilbur Minafer's funeral. This would, as Robert L. Carringer notes, get on more directly with the development of George and Lucy's relationship -- and perhaps compensate somewhat for the loss of the development of their relationship as they sit on the stairs at the end of the ball. At any rate, this was not done -- both scenes remained later in the picture -- but another of Welles's edits was implemented: At Wilbur's death, instead of the shot of Wilbur's tombstone that was in place, he ordered a new shot of townspeople, with one saying "Wilbur Minafer -- Quiet man -- Town will hardly know he's gone." ("Phone me to get correct reading for line.") In the release version the line is spoken by Erskine Sanford as Roger Bronson.

At Welles's direction, a shot of George Minafer's diploma was cut, which leads to some inevitable confusion in the beginning of the kitchen scene between Fanny and George (and later Jack); at first it seems to follow Wilbur's funeral rather than coming months later after George's graduation and return home. This is probably unavoidable since George's life at college, and Jack, Isabel and Eugene attending his commencement -- all of which is in the novel -- was never shot. Welles also directed that the kitchen scene end before George sees the construction outside in the yard, and this was also done in the final version.

Welles called for keeping the first porch scene, ending it before George's fantasies about Lucy, but the scene remained out.

As for the "big cut" that so truncated the lingering death of Isabel Amberson Minafer, and which Moss and Wise had restored for the Pasadena preview, Welles wanted that footage taken out again, with other changes and reshoots that he felt would improve what remained. But he had evidently had second thoughts about the Moss-Wise-Cotten compromise plan he had dismissed out of hand on March 25, and now was willing to go along with some of their suggestions, especially the major restructuring after Isabel's death: Jack and George's farewell at the railroad station, the "Indian legend" scene with Lucy and Eugene, the scene of Fanny's breakdown as she and George discuss their financial straits, George in Bronson's office giving up his hopes for a career in law, and George's last walk home to Amberson Mansion, where he gets his come-uppance ("Mother, forgive me ... God, forgive me.")

In a letter to Welles dated March 31, Robert Wise summarized the audience reaction at both previews ("I have never tackled a more difficult chore ... it's so damn hard to put on paper in cold type the many times you die through the showing...") Wise went through the picture step by step; he didn't always distinguish between one audience and the other, but he made a point to say how well some of the "big cut" scenes had played, which the Pomona crowd hadn't seen but the Pasadena audience had. Wise again emphasized the problematic nature of the last scene between Fanny and Eugene: "The boarding house got us several laughs, one on the man's face when the door opens and several through the scene on Fanny's strange behavior, and here again we could feel great restlessness."

Welles was determined to retain the boarding house scene, and he thought he had the solution to everyone's concerns. It would come in the closing credits, which were to be spoken by Welles with shots illustrating each name as it came up. "To leave audience happy for Ambersons," he wired Jack Moss on April 2, "remake cast credits as follows..." First he wanted an oval framed picture of Richard Bennett "in Civil War campaign hat", presumably made up to look younger than he does in the movie itself; then, "live shot of Ray Collins ... in elegant white ducks and hair whiter than normal seated on tropical veranda ocean and waving palm trees behind him ... [then, Agnes Moorehead] blissfully and busily playing bridge with cronies in boarding house." And so on, down to Joseph Cotten looking out a window at Tim Holt and Anne Baxter as they drive away, waving at Eugene/Joseph behind them: " ... they turn to each other then forward both very happy and gay and attractive for fadeout."

"As solutions go," says Prof. Carringer, "this one could only have raised doubts about how fully Welles comprehended the gravity of the situation." Indeed so, if Welles thought he could win an audience over with a cheerful curtain call of George/Tim and Lucy/Anne waving and smiling at the audience as they drive off into the sunset. This would surely register only as a breezy non sequitur. The same goes for Welles's intention to show Richard Bennett in a Civil War uniform or Ray Collins basking on a tropical beach; these poses would have looked particularly odd since no version of the picture ever referred to Major Amberson's Civil War service or Uncle Jack's obtaining a South American consulship. To someone who had just sat through the picture, it would look as if Richard Bennett was dressed for a costume party and Ray Collins off on a vacation from Hollywood; if an audience was inclined to laugh at The Magnificent Ambersons, none of this would have persuaded them to stifle their giggles. In the end this suggestion was not followed; the cast list showed the actors in medium closeup, turning to regard the camera with friendly half-smiles.

There is in fact some reason to believe that Robert Wise had begun to think Welles had lost touch with the picture. "I've always felt," Wise said years later, "that if Orson had been at the preview and had seen and heard that reaction, he'd have understood better what did and didn't work in it. As it was, Mark Robson and I were in touch with him almost every day, these long, long telegrams -- 20, 30 pages sometimes. It would have been so much easier if he could have been there." Schaefer -- deciding, perhaps, that the law of diminishing returns was kicking in -- called a temporary halt to any activity on Ambersons, to let Wise, Robson and Moss recharge their batteries, and to try to reach some agreement with Welles.

Adding to the fear that Welles had lost touch with Ambersons was the very real fact that he seemed to have lost control of It's All True -- if, indeed, he'd ever had control of it in the first place. After Carnival, the weather in Rio had turned awful and wouldn't let up -- constant bitter cold and thundering rains that made outdoor shooting impossible. An expected shipment of supplies and equipment seemed endlessly delayed. The crew idled and grumbled, piddling along with what interior pickup shots could be managed, often without Welles even being present, and with little sense of exactly what they were shooting (when they were shooting) or why. "Everything here proceeding beautifully," Welles blithely wired Schaefer, but production manager Lynn Shores -- a querulous, irascible man who was virtually a spy for the anti-Welles faction at RKO -- painted a much bleaker picture. Shores carped about everything, from spending all night in "meaningless conferences" with Welles to having to be the one calling "action" and "cut" when Orson wasn't around. Shores, ever the proud martyr, portrayed himself as the only thing standing between the crew and demoralized, mutinous chaos.

Schaefer probably knew to consider the source, but enough reports were coming in from second, third and fourth parties to suggest that Shores's sour perspective was closer to the truth than Welles's. Finally, in mid-April, Schaefer transferred full responsibility for editing Ambersons to Robert Wise and told him just to do whatever was necessary to get the picture in a releasable form.

Actors were called back to shoot retakes and new inserts. There was a new scene (directed by Wise) between George and Isabel after they've read Eugene's letter, omitting or softening some of George's wilder overreactions ("It's simply the most offensive piece of writing that I've ever held in my hands ... if he ever set foot in this house again ... I ... I can't speak of it."). A scene (by assistant director Freddie Fleck) of Eugene being turned away by George, Fanny and Jack as Isabel lies dying upstairs. A shortened opening (directed by Jack Moss) for the scene between George and the hysterical Fanny in the empty Amberson Mansion. Another scene (Fleck again) in which first Lucy, then Eugene, decide to visit George in the hospital after his auto accident.

Two scenes -- (1) the buggy ride scene, where George and Lucy quarrel over George's reluctance to "make something of himself", and (2) the following carriage scene between Uncle Jack and Major Amberson, talking about the changes in their town and the decline in the family fortune -- Welles wanted to move to much earlier, before Wilbur Minafer's funeral. This would, as Robert L. Carringer notes, get on more directly with the development of George and Lucy's relationship -- and perhaps compensate somewhat for the loss of the development of their relationship as they sit on the stairs at the end of the ball. At any rate, this was not done -- both scenes remained later in the picture -- but another of Welles's edits was implemented: At Wilbur's death, instead of the shot of Wilbur's tombstone that was in place, he ordered a new shot of townspeople, with one saying "Wilbur Minafer -- Quiet man -- Town will hardly know he's gone." ("Phone me to get correct reading for line.") In the release version the line is spoken by Erskine Sanford as Roger Bronson.

At Welles's direction, a shot of George Minafer's diploma was cut, which leads to some inevitable confusion in the beginning of the kitchen scene between Fanny and George (and later Jack); at first it seems to follow Wilbur's funeral rather than coming months later after George's graduation and return home. This is probably unavoidable since George's life at college, and Jack, Isabel and Eugene attending his commencement -- all of which is in the novel -- was never shot. Welles also directed that the kitchen scene end before George sees the construction outside in the yard, and this was also done in the final version.

Welles called for keeping the first porch scene, ending it before George's fantasies about Lucy, but the scene remained out.

As for the "big cut" that so truncated the lingering death of Isabel Amberson Minafer, and which Moss and Wise had restored for the Pasadena preview, Welles wanted that footage taken out again, with other changes and reshoots that he felt would improve what remained. But he had evidently had second thoughts about the Moss-Wise-Cotten compromise plan he had dismissed out of hand on March 25, and now was willing to go along with some of their suggestions, especially the major restructuring after Isabel's death: Jack and George's farewell at the railroad station, the "Indian legend" scene with Lucy and Eugene, the scene of Fanny's breakdown as she and George discuss their financial straits, George in Bronson's office giving up his hopes for a career in law, and George's last walk home to Amberson Mansion, where he gets his come-uppance ("Mother, forgive me ... God, forgive me.")

In a letter to Welles dated March 31, Robert Wise summarized the audience reaction at both previews ("I have never tackled a more difficult chore ... it's so damn hard to put on paper in cold type the many times you die through the showing...") Wise went through the picture step by step; he didn't always distinguish between one audience and the other, but he made a point to say how well some of the "big cut" scenes had played, which the Pomona crowd hadn't seen but the Pasadena audience had. Wise again emphasized the problematic nature of the last scene between Fanny and Eugene: "The boarding house got us several laughs, one on the man's face when the door opens and several through the scene on Fanny's strange behavior, and here again we could feel great restlessness."

"As solutions go," says Prof. Carringer, "this one could only have raised doubts about how fully Welles comprehended the gravity of the situation." Indeed so, if Welles thought he could win an audience over with a cheerful curtain call of George/Tim and Lucy/Anne waving and smiling at the audience as they drive off into the sunset. This would surely register only as a breezy non sequitur. The same goes for Welles's intention to show Richard Bennett in a Civil War uniform or Ray Collins basking on a tropical beach; these poses would have looked particularly odd since no version of the picture ever referred to Major Amberson's Civil War service or Uncle Jack's obtaining a South American consulship. To someone who had just sat through the picture, it would look as if Richard Bennett was dressed for a costume party and Ray Collins off on a vacation from Hollywood; if an audience was inclined to laugh at The Magnificent Ambersons, none of this would have persuaded them to stifle their giggles. In the end this suggestion was not followed; the cast list showed the actors in medium closeup, turning to regard the camera with friendly half-smiles.

There is in fact some reason to believe that Robert Wise had begun to think Welles had lost touch with the picture. "I've always felt," Wise said years later, "that if Orson had been at the preview and had seen and heard that reaction, he'd have understood better what did and didn't work in it. As it was, Mark Robson and I were in touch with him almost every day, these long, long telegrams -- 20, 30 pages sometimes. It would have been so much easier if he could have been there." Schaefer -- deciding, perhaps, that the law of diminishing returns was kicking in -- called a temporary halt to any activity on Ambersons, to let Wise, Robson and Moss recharge their batteries, and to try to reach some agreement with Welles.

Adding to the fear that Welles had lost touch with Ambersons was the very real fact that he seemed to have lost control of It's All True -- if, indeed, he'd ever had control of it in the first place. After Carnival, the weather in Rio had turned awful and wouldn't let up -- constant bitter cold and thundering rains that made outdoor shooting impossible. An expected shipment of supplies and equipment seemed endlessly delayed. The crew idled and grumbled, piddling along with what interior pickup shots could be managed, often without Welles even being present, and with little sense of exactly what they were shooting (when they were shooting) or why. "Everything here proceeding beautifully," Welles blithely wired Schaefer, but production manager Lynn Shores -- a querulous, irascible man who was virtually a spy for the anti-Welles faction at RKO -- painted a much bleaker picture. Shores carped about everything, from spending all night in "meaningless conferences" with Welles to having to be the one calling "action" and "cut" when Orson wasn't around. Shores, ever the proud martyr, portrayed himself as the only thing standing between the crew and demoralized, mutinous chaos.

Schaefer probably knew to consider the source, but enough reports were coming in from second, third and fourth parties to suggest that Shores's sour perspective was closer to the truth than Welles's. Finally, in mid-April, Schaefer transferred full responsibility for editing Ambersons to Robert Wise and told him just to do whatever was necessary to get the picture in a releasable form.

Actors were called back to shoot retakes and new inserts. There was a new scene (directed by Wise) between George and Isabel after they've read Eugene's letter, omitting or softening some of George's wilder overreactions ("It's simply the most offensive piece of writing that I've ever held in my hands ... if he ever set foot in this house again ... I ... I can't speak of it."). A scene (by assistant director Freddie Fleck) of Eugene being turned away by George, Fanny and Jack as Isabel lies dying upstairs. A shortened opening (directed by Jack Moss) for the scene between George and the hysterical Fanny in the empty Amberson Mansion. Another scene (Fleck again) in which first Lucy, then Eugene, decide to visit George in the hospital after his auto accident.

And, most notoriously, this. Audience reaction and response cards had convinced everyone but Welles that his beloved boarding house scene had to go, so it was replaced with this one between Eugene and Fanny in the corridor outside George's hospital room. Much of the dialogue was the same, but with a more upbeat reading from Joseph Cotten and a more serenely blissful reaction from Agnes Moorehead; the result was closer to Tarkington's ending -- though a far cry from the melancholy, even sullen tone that Welles had so carefully set, and which Joseph Cotten had found more Chekhov than Tarkington. Simon Callow says this scene was directed by Jack Moss; Prof. Carringer says it was Freddie Fleck. But whoever was responsible, they both hate it, as does nearly everybody who's ever had an opinion on Ambersons.

For the music in this and other new scenes, composer Bernard Herrmann was not consulted. Instead, the studio brought in Roy Webb, more malleable than the notoriously prickly Herrmann, albeit vastly less talented. In the end, 30 of the 56 minutes Herrmann had written were used, supplemented by 6 minutes 45 seconds from Webb. The furious Herrmann threatened to sue unless his name was removed from the picture, and he got his way.

Another recut of Ambersons (running time unknown) was previewed in Inglewood on May 4, and yet another (87 minutes) in Long Beach on May 12, with (according to Prof. Carringer) "encouraging results". But by now, Charles Koerner and his anti-Welles faction were only too eager to stick their thumbs in the Ambersons pie; Schaefer, Wise and Moss were forced into a rear-guard action to try to preserve what they could (within a 90-minute deadline) of the great movie they knew was in there somewhere. Moss was a fish out of water whom nobody outside Mercury Productions regarded with even an ounce of respect. Schaefer, outflanked by Koerner, was increasingly a dead man walking the halls at RKO. The struggle fell largely to Wise, since he was the man most intimately familiar with all the footage, and the one whose job at the studio ultimately proved much more secure than either Moss's or Schaefer's. The cutting and pasting continued -- this scene out, that scene in, this one trimmed, that one moved, another back in, another back out -- as The Magnificent Ambersons inched ever closer to final form, the form (with a few minor differences) proposed in the "compromise" version worked out by Robert Wise, Jack Moss and Joseph Cotten and wired to Welles on March 23. Finally, Schaefer ordered a handful of last-minute tweaks and a print was shipped to him in New York on June 5. Three days later Schaefer screened the print and approved it for release. The picture now ran 88 minutes 10 seconds.

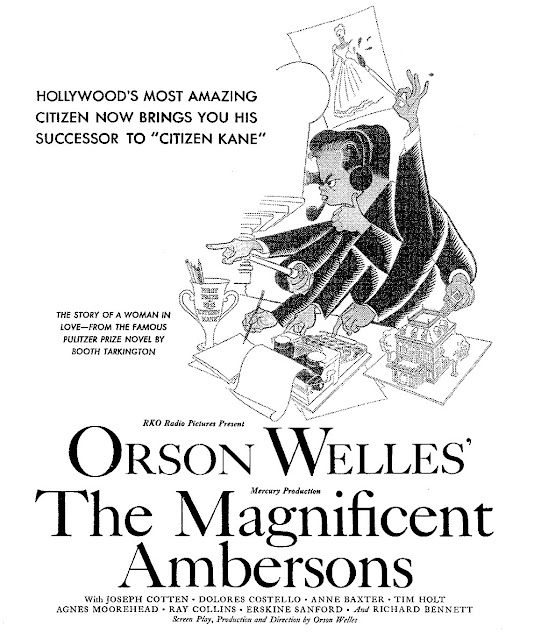

The Magnificent Ambersons finally saw release on July 10, missing not only Easter Week, but Memorial Day, Flag Day and the Fourth of July as well. And forget Radio City Music Hall; in New York it played the 4,000-seat Capitol -- still a picture palace, but hardly the RKO flagship. And not all of the picture's play dates were that prestigious; in some places it ran on a double bill with Lupe Velez in Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost -- with Ambersons as the bottom half. Despite RKO's malign neglect and a $625,000 loss, the picture impressed enough Academy voters by early 1943 to garner four Oscar nominations: for best picture, best art direction/interior decoration, Stanley Cortez's cinematography, and Agnes Moorehead's harrowing performance as the neurotic, sexually frustrated Fanny.

But even before the picture's release, the game was up. George Schaefer, maneuvered by Charles Koerner into a lame duck, finally resigned on June 26. Koerner had been stewing since May over a report from the budget office that It's All True had cost $526,000 so far and would take at least another $595,000 to finish; now, finally rid of Schaefer, Koerner pounced. He cut off Welles's money and ordered the unit back to Hollywood forthwith. When Welles, enthusiastic about the Four Men on a Raft episode he was currently involved in, pleaded to finish it, Koerner granted him $10,000, one camera, and 40,000 feet of film; let him see how long that would last. Finally, the killing blow: Koerner evicted Mercury Productions from the RKO lot, giving them 24 hours to vacate the premises. In a telegram from Brazil, Welles tried to buck up his people's spirits: "Don't get excited. We're just passing a rough Koerner on our way to immortality." In rebuttal, the Koerner faction had a pun of their own: "All's well that ends Welles."

The Magnificent Ambersons finally saw release on July 10, missing not only Easter Week, but Memorial Day, Flag Day and the Fourth of July as well. And forget Radio City Music Hall; in New York it played the 4,000-seat Capitol -- still a picture palace, but hardly the RKO flagship. And not all of the picture's play dates were that prestigious; in some places it ran on a double bill with Lupe Velez in Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost -- with Ambersons as the bottom half. Despite RKO's malign neglect and a $625,000 loss, the picture impressed enough Academy voters by early 1943 to garner four Oscar nominations: for best picture, best art direction/interior decoration, Stanley Cortez's cinematography, and Agnes Moorehead's harrowing performance as the neurotic, sexually frustrated Fanny.

But even before the picture's release, the game was up. George Schaefer, maneuvered by Charles Koerner into a lame duck, finally resigned on June 26. Koerner had been stewing since May over a report from the budget office that It's All True had cost $526,000 so far and would take at least another $595,000 to finish; now, finally rid of Schaefer, Koerner pounced. He cut off Welles's money and ordered the unit back to Hollywood forthwith. When Welles, enthusiastic about the Four Men on a Raft episode he was currently involved in, pleaded to finish it, Koerner granted him $10,000, one camera, and 40,000 feet of film; let him see how long that would last. Finally, the killing blow: Koerner evicted Mercury Productions from the RKO lot, giving them 24 hours to vacate the premises. In a telegram from Brazil, Welles tried to buck up his people's spirits: "Don't get excited. We're just passing a rough Koerner on our way to immortality." In rebuttal, the Koerner faction had a pun of their own: "All's well that ends Welles."

4 comments:

Orson Welles must have been on drugs! How delusional can one man be? Oh, and I see you're still not done. Are you writing a book?

Just want you to know this is a fantastic series, Jim. I just saw the film for the first time last month and so it's very fresh in my mind as I read all your comments. Thank you for this great slice of movie history!

Best wishes,

Laura

Jim,

So much has been written about Orson's perfection, need to edit, cut, reshoot his films and you've certainly given us some amazing examples here.

I've been waiting patiently for your Part 5 and I have to say it was worth the wait.

I can imagine that the scenes, footage cut from Welle's films triple what was left for movie goers to enjoy.

Thanks for including a couple of still shots from those scenes.

I plan to go back and watch TMA once your series is complete. I'll certainly see it in a different light and most definitely appreciate it more knowing what you've provided with us here.

Truly enjoyable Jim and I do hope you'll choose another one of Orson's films to do this type of series, pick it apart and analyze it if you will.

Have a great weekend!

Page

Jim, I think Kim is onto something: with all the amazing work you've done on this astounding MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS blog series, you really should consider turning this into a book, if you're not already exhausted from the sheer scope of this series! :-)

It blows my mind how crazily complicated it must have been to work with the peripatetic Orson Welles and the people in his orbit trying to keep up with him! No wonder the RKO brass were going nuts!

One of the things that bewilders me as a lover of both movies and books is: why the hell did Welles want to essentially turn a Booth Tarkington novel into a Chekhov play? Call me a Philistine, but why not keep ...AMBERSONS true to its source material? I mean, if I want to read Tarkington, I'll read Tarkington, and if I want to read a Chekhov play, I'll read a Chekhov play! If it ain't broke, why "fix" it? Was it just sheer arrogance on Welles' part, or what?

Forgive my ramblings, Jim, but consider this a compliment to you for giving me so much food for thought. I can hardly wait to see how all this winds up! Great job, my friend, as always!

Post a Comment